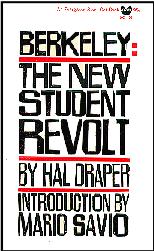

Berkeley: The New Student Revolt

by Hal DraperChapters 1 to 10 (out of 43)

1

A New Generation of Students"

From the middle of September 1964 until the end of the year, followed by an armistice-like lull in January, the University of California campus at Berkeley was the scene of the largest-scale war between students and administration ever seen in the United States. It was also the scene of the largest-scale victory ever won in such a battle by students, organized as the Free Speech Movement.

It had everything in terms of American superlatives: the largest and longest mass blockade of a police operation ever seen, the biggest mobilization of police force ever set up on any campus; the biggest mass arrest ever made in California, or of students, or perhaps ever made in the country; the most massive student stake ever organized here. It was, in sum, by far the most gigantic student protest movement ever mounted in the United States on a single campus.

There must have been a reason -- an equally gigantic reason. Berkeley gets the most brilliant students in California, by and large, and a good portion of the best from the rest of the country. In turn, the FSM included a good portion of the best at Berkeley.

'The real question" said the head of the university's History Department, Professor Henry May, "is why such a large number of students -- and many of them our best students, who have engaged in no prior political activity -- followed the Free Speech leaders."

A professor who thought the FSM's sit-in tactics were "anarchy," Roger Stanier, nevertheless admitted that the state's governor was wrong in thinking that "the dissident students constitute a small radical fringe." He declared, "This is simply not the case. Some of the most able, distinguished students at the university are involved in this matter."

The chairman of the university's Classics Department, Joseph Fontenrose, wrote to a daily paper that "The FSM leaders represent a new generation of students ... They are good students; serious, dedicated, responsible, committed to democratic ideals."

Life magazine's columnist Shana Alexander seemed rather surprised to report from the field that "the FSMers I met were all serious students, idealists, bright even by Berkeley's high standards, and passionate about civil rights. Although, regrettably, they neither dress nor sound one bit like Martin Luther King, they do feel like him." (Jan 15, 1965.)

In a survey of the FSM students who were arrested in the mass sit-in of December 3, it was found that:

Most are earnest students of considerably better than average academic standing.... Of the undergraduates arrested, nearly half (47% ) had better than 3.0 (B) averages, 71% of the graduate students had averages above 3.5 (between B and A). Comparable figures for the undergraduate and graduate student bodies as a whole, according to the Registrar's Office, are 20% and 50%, respectively. Twenty were Phi Beta Kappa; eight were Woodrow Wilson fellows; twenty have published articles in scholarly journals; 53 were National MeAt Scholarship winners or finalists; and 260 have received other academic awards. Not only are these students among the brightest in the University, but they are also among the most advanced in their academic careers. Nearly two-thirds (64.3%) are upper-division or graduate students. (Graduate Political Scientists' Report.*)

A similar result was found in a survey of student opinion made in November under the supervision of a sociology professor, Robert Somers. Of those interviewed who had a grade point average of B+ or better, nearly half (45% ) were pro- FSM, and only a tenth were anti-FSM; but of those with B or less, over a third were anti-FSM and only 15% were pro.** We shall also see later that the "elite" of the graduate students, those given jobs as Teaching Assistants and Research Assistants, had a far higher proportion of commitment to the FSM than the graduate body as a whole. In terms of student quality, the higher a student stood in accomplishment or level of training, the more likely was he to be pro-FSM to one degree or another.

These are rather mind-shaking facts for those journalistic or professorial commentators whose reflex reaction to the outbreak of Berkeley's Time of Troubles was to derogate the "trouble-makers" as "a bunch of rowdies," "unwashed beatniks," "forlorn crackpots" or with other profound epithets.

Perhaps more surprising to some is the fact that, in spite of some feeble efforts at McCarthy-type redbaiting -- by University President Clark Kerr, by Professor Lewis Feuer, and by some local politicians -- even lunatic fringe elements apparently decided that the FSM was really and truly not Communist-led. At one FSM rally the local fuehrer of Rockwell's American Nazis held aloft a placard with the announcement "Mario Savio Is a Dupe of Communism," which translated means that the FSM leader could not possibly be a Communist. Of course, to hand the Communist Party (which is insignificant in influence in the Bay Area) credit for a great democratic student movement would be an ultimate commentary on the self-destructiveness of the American obsession with "anti-Communism" as a substitute for politics.

A student revolt of these massive proportions is a phenomenon of national importance. It demands to be studied, analyzed, and understood, whether by students who want to go and do likewise, or by educators who want to remedy the conditions which produced it, or by observers who want to grasp what is happening to the Great Society of the sixties.

* This is the short title of the following document: The Berkeley Free Speech Controversy (Preliminary Report). Prepared by: A Fact-Finding Committee of Graduate Political Scientists (E. Bardach, J. Citrin, E. Eisenbach, D. Elkins, S. Ferguson, R. Jervis, E. Levine, P. Sniderman), December 13, 1964. (Mimeo.) The viewpoint of these graduate students is pro-FSM, but their work is a valuable compilation of information and data.

** We shall refer to this again as Somers' November survey. He based his report, issued in January, on "a carefully drawn sample of 285 students representing the whole student body."

2

The Liberal Bureaucrat

To some it is a mystery that the Berkeley revolt should have broken out against the "liberal" administration of President Clark Kerr, in the state-wide university, and of Chancellor Edward Strong as chief officer of the Berkeley campus. Both are liberals, to be sure, as liberals go nowadays; but what is most clearly liberal about them is their pasts.

In his student days, indeed, Kerr was what is now sometimes called a "peacenik," and even joined the socialist Student League for Industrial Democracy. Liberalism is the direction from which Kerr has been evolving. In his 1960 book, Industrialism and Industrial Man, Kerr intimates quite clearly that he has been going through a process of changing his "original convictions," but this does not necessarily involve any conscious abandonment of liberalism as the framework for his rhetoric. What he has been superimposing on this framework is a newly embraced concept of bureaucratic managerialism as the social model to be accepted. The bureaucratization of Kerr's thought has been held in balance with liberalism only in the sense that he looks forward to a Bureaucratic Society which retains adventitious aspects of liberalism in the interstices of the social system.

I do not know how long this social world view had been growing on Kerr; but its first publication occurred in an article on "The Structuring of the Labor Force in Industrial Society" (written in collaboration with A. J. Siegel), published in January 1955. Since his central concept is the role of the bureaucracy (for Kerr, the bureaucracy is the Vanguard of the Future in the same sense, he tells us, as the working class was for Marx), it is interesting to note that Kerr himself definitely rose into the upper ranks of the Multiversity bureauracy in mid-1952, when he became chancellor at Berkeley, after directing the Institute of Industrial Relations since 1945. The article mentioned was written within two years after this ascension. The fuller flowering of this world view in his subsequent book came within two years after his further ascension to the presidency in 1958, when he became (in his own term) "Captain of the Bureaucracy."

People who think of Kerr as a liberal, but who have not paid attention to his most recent societal lucubrations, tend to be incredulous when told that the new Kerr views systemic and systematic bureaucratism as the new revelation. The population living under his Multiversity, however, had to take this as seriously as does Kerr himself.

Failure to understand the theoretician of the Multiversity is one source of the myth that the student revolt burst out against a particularly liberal administration. Another source is misconception of what has happened on the Berkeley campus under Kerr's administration.

3

Behind the Myth of Liberalization

The previous president, Robert G. Sproul, had been a reactionary bureaucrat, not a liberal bureaucrat. It was in his reign, of course, that Berkeley had gone through the shattering "Year of the Oath" -- the subjection of the faculty to a McCarthyite loyalty oath; the long fight of the faculty against this indignity, to which most ended up by capitulating; the loss of some of the most eminent men on the faculty, who left rather than disgrace themselves and their profession. (Kerr in those days played a role much appreciated by the faculty, not as a militant non-signer but as a mediator, and this strongly influenced his accession as chancellor in 1952.)

One of the by-product virtues of a reactionary is that you are more likely to know just where you stand with him. Sproul's stand on political discussion and social action as far as students were concerned was straightforward: it was all banned, except at the pleasure of the administration. In accordance with his notorious "Rule 17," even Adlai Stevenson could not speak on campus, and Norman Thomas was likewise not permitted to subvert the state constitution by speaking inside Sather Gate.

As the nation and even California emerged more and more from the miasma of the McCarthyite era, as the "Silent Generation" of students became vocal, this blunt know-nothingism became more and more intolerable, i.e., was obviously leading to a blowup. In fact, the rule was eased in the fall of 1957 under Sproul himself and after Kerr became president the next year, an entirely different tack was taken to keep political discussion and action under control on the campus. The key was not a brusque ban but administrative manipulation accompanied by libertarian rhetoric. The "Kerr Directives" of 1959 liberalized some aspects of Sproul's regime (no difficult achievement) but, even with later modfications, actually worsened others.*

During the next five years of Kerr's regime, student activists complained of a long series of harassments. Here are some highlights:

The student government (ASUC -- Associated Students of the University of California) was forbidden to take stands on "off-campus" issues, except as permitted by the administration, and was effectively converted to a "sandbox" government.

Graduate students -- over a third of the student body -- were disfranchised, excluded from the ASUC, by a series of manipulations.

Political-interest and social-issue clubs were misleadingly labeled "off-campus clubs" and forbidden to hold most organizational meetings on campus, or to collect funds or recruit. ("On many campuses all student groups can use equally the offices, equipment, secretarial staff and other facilities provided by their student governments. At Cal these privileges are reserved for non-controversial groups such as the hiking and yachting clubs," explained FSM Newsletter, No. 1.)

Groups like the Republican "Students for Lodge" and "Students for Scranton" could not even put the names of their candidates on posters.

Club posters were censored on other grounds of political content.

Outside speakers were not permitted except on a 72-hour-notification basis.

Clubs could not, in practice, schedule a connected series of discussions or classes at all.

Off-campus activities could not be announced at impromptu rallies.

Malcolm X, then a Black Muslim leader, was at first banned from speaking on campus, and eventually permitted to speak only after an uproar.

Students for Racial Equality were forbidden to use $900 collected to establish a scholarship for a Negro student expelled from a Southern university.

The clubs were forbidden to hold campus meetings in support of a Fair Housing Ordinance on the ballot in the city of Berkeley.

In 1960, virtually the whole staff of the Daily Californian resigned in protest when a docile ASUC, instigated by the administration, clamped down on the newspaper's endorsement of Slate candidates and its attention to "off-campus" issues.

So it went. This is the campus which some, later, claimed to be "the freest campus in the country." **

In a somewhat different field, it is relevant to note that in 1962 the California Labor Federation (state AFL-CIO) -- under one of the most conservative state readerships in the country -- adopted a convention resolution condemning the university administration and Regents for their "antiquated labor relations philosophy" which, it said, "lags far behind the standards established through collective bargaining in private industry." The resolution cited experiences with the "countless roadblocks" thrown up by the administration against union activities. The unions' complaints about treatment by the university are remarkably similar to the students'.

* A fully documented study, Administrative Pressures and Student Political Activity at the University of California: A Preliminary Report, edited by Michael Rossman and Lynne Hollander, was issued by the FSM in December 1964. The introductory summary was distributed separately; the complete report is a thick document made up of forty studies, mostly on issues during Kerr's administration, but also taking up the loyalty- oath fight of 1949-58. Also see the article "Yesterday's Discords" by Max Heinrich and Sam Kaplan, in the California Monthly (alumni magazine), February 1965.

** On this claim, cf. the California Monthly article "Yesterday's Discord," reporting on the 1962-63 academic year: "The ASUC, while continuing to abide by the Kerr Directives, sought ... to learn whether schools similar to U.C. had comparable regulations. It found in a survey of 20 schools with student bodies of more than 8,000 that only one, the University of Arizona, had similarly restrictive rules." For a similar report, see the summary in Time, December 18, 1964, beginning: "By and large, restrictions are the mark of small, church-affiliated colleges intent on serving in loco parentis, while freedom for students, defined roughly as the rights and curbs of ordinary civil law, is the goal at big, old, and scholastically high-ranking state and private universities." After a survey it concludes: "Berkeley students have blown off the lid. It now remains for them to follow the tradition of schools that have long allowed a wide range of undergraduate freedom." In the Bay Area itself, even San Francisco State College, operating under the same state legislature as the more prestigious university, imposed none of the restrictions against which the Berkeley students revolted.

4

The Myth: Two Showpieces

There are two showpieces of Kerr's administrative liberalism, a consideration of which will complete the picture. Kerr supporters constantly cite these two items, in addition to equating the decline of McCarthyite pressures with advances in liberalization.

In 1960 occurred the famous student "riot" or "demonstration" (depending on your view) at the San Francisco City Hall, against the House Committee on Un-American Activities hearing. Discriminatory exclusion of students from the hearing room helped to turn the demonstration into a shambles; then the police opened up powerful water hoses to batter the students down the City Hall stairs. Mass arrests followed.

When rightwingers called for the expulsion of the arrested students, Kerr replied that they had acted in their capacity as citizens and were not liable to the university for their conduct. For this he was cheered by liberals.

It was not much noticed at the time that Kerr inserted a basic qualification into his stand. If the action had been planned on campus, he indicated, then university disciplinary action would be in order. In 1964 he was going to put sharp teeth into what had seemed in 1960 to be a principled defense of liberalism.

There was a sequel to the HUAC episode, particularly involving the notorious film Operation Abolition. The administration evidently had expended so much courage in refusing to expel the anti-HUAC students that there was little left in the next pinch. The law students' club at Berkeley proposed to show Operation Abolition together with a talk on it by Professor John Searle. Searle was forbidden to speak unrebutted, on the ground that his speech would be controversial yet the administration was willing to allow the pro-HUAC fiim to be shown by itself, presumably because it was not controversial. After the student "party," Slate, produced a record ("Sounds of Protest") as a reply to the film, the administration began a harassment campaign which resulted in Slate's losing its "on- campus" status -- as the California McCarthyite, State Senator Burns, had predicted in advance. The harassment of the Daily Cal, which resulted in the mass resignation of its staff, was also in part due to the attention which the newspaper had paid to the HUAC issue.

The second showpiece was the Regents' removal, in 1963, of the ban against Communist speakers on campus. Kerr was later (January 1965) going to use this move as proof that "Demonstrations do not speed administrative changes," for, he argued, the Communist-speaker ban was removed without FSM rallies, sit-ins or strikes.

In this capsule-history Kerr omitted the long series of student protests, rallies, polls, ASUC and club petitions, and other pressures organized against the ban after 1960 in Berkeley, especially in 1962. He also ignored the increasing realization, even by conservatives, that the ban only served to ensure big off-campus audiences for the Communist speakers banned, as well as misplaced sympathy. Moreover, in February 1963 the faculty itself was gravely embarrassed when the administration forbade even the History Department from listening to the Communist Party writer Herbert Aptheker, who had been invited to give an academic talk in the field of Negro history. It was becoming ridiculous.

Even so, the Regents were not induced to "Ban the Ban" until a court test, started by a Riverside campus student group, threatened to bring a ruling from the State Supreme Court which would force their hand. They then finally agreed to end the ban voluntarily, rather than risk reversal by the courts, and the suit was dropped.

But this is not the end of this story of administrative liberalism. In the same action which abolished the special ban on Communist speakers, Kerr proclaimed new harassing rules aimed against all "controversial" speakers. Henceforth, the administration could require, at its pleasure, that any meeting with an outside speaker be chaired by a tenured professor, allegedly in order to ensure its "educational" character. The purely harassing intent of this regulation was adequately expressed by the proviso (tenure) which excluded even assistant professors from fulfilling the requirement. There has never been an explanation of why a meeting is less "educational" if chaired by an assistant professor than by an associate or full professor.* As a result, many a meeting had to be canceled or transferred off-campus when no tenured professor could be induced to spend an evening of his time satisfying Kerr's "liberalized" rules.

By combining this nuisance rule and some minor ones with the much-praised abolition of the Communist-speaker ban, so that the former went through with little notice among the chorus of amens that rose over the latter, Kerr showed a mastery of administrative manipulation which merits admiration. He received more than admiration: he was given the Alexander Meiklejohn award by the American Association of University Professors for contributions to academic freedom.

Nor was the tenured-professor stratagem the only rule thrown at "controversial" speakers. Around the spring of 1964 the administration invented the practice of assigning policemen to "protect" meetings deemed to be "controversial" -- even though not requested and not needed -- and then charging the sponsoring club from about $20 or $40 up to $100 for the privilege. (At the same time, the club was forbidden to take any collection to pay for this hard blow to its usually meager finances.) As Campus CORE put it in a leaflet reproducing such a bill: "forcing people to pay for protection from non- existent dangers is extortion ... The administration is pushing us off campus with its protection."

But it was not any of this that led directly to the explosion. All of this was, so to speak, routine administrative harassment of free speech and political activity.

* But a revealing modification of the tenured-professor rule was later (December) instituted at UCLA. New regulations required a tenured chairman only "in the case of speakers representing social or political points of view substantially at variance with established social and political traditions in the U.S." Thus the conditions for "free speech" are here officially made dependent on a speaker's support of or disagreement with the American Party Line.

5

The Power Structure Triggers the Conflict

The storm was brewing from another quarter.

This is the place to make clear that one would be wrong to conclude from the preceding history that President Kerr himself had any dislike for "controversial" speeches, student political activity, or "free speech." * On the contrary; he is, after all, a kind of liberal. When he writes his eloquent addresses about not making "ideas safe for students, but students safe for ideas," etc., he means every word of it. It is a Great Ideal, and he firmly believes it should be talked about on every possible ceremonial occasion.

But Kerr is sensitive to the real relations between Ideals and Power in our society. Ideals are what you are for, inside your skull, while your knees are bowing to Power. This is not cynicism to Kerr; he has a theory about the role of the Multiversity president as a mediator among Powers. It is no part of a mediator's task to dress up as Galahad and break a lance against dragons. In fact, if a Galahad does show up, he may only be an annoyance to the mediator, since this introduces a third, complicating party to the dispute between the dragon and his prey.

The students' onslaught against HUAC had stirred up dragons -- forked-tongue monsters from Birchites to Republican assemblymen -- breathing fire against the university authorities who were "protecting" all those "Communist" students. Holding the fort against these made one feel like a courageous liberal; and if a Professor Searle was going to take up the lance, he would only enrage the animals -- slap him down.

In 1963 and 1964, from the viewpoint of the University mediator, a frightening thing was happening: there was a growing movement on campus devoted to systematically provoking and stirring up every dragon within fifty miles. This was the civil-rights movement.

The Friends of SNCC were collecting money for Mississippi project workers. But Campus CORE and Berkeley CORE were engaged in local projects: for example, picketing and signing fair-hiring agreements with the Shattuck Avenue (central Berkeley) merchants, and with Telegraph Avenue. (campus district) businessmen. Then there was the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination, not a campus group but supported by many students.

In November 1963 came the first mass-picketing of a commercial firm charged with discrimination in hiring, Mel's Drive-In restaurants on both sides of the bay. Many university students were involved when police arrested 111 in San Francisco. Berkeley CORE engaged in Christmas picketing of campus-district stores. In February, Campus CORE (formed the previous September) took on the local branch of Lucky Supermarkets, as part of an area-wide campaign against the store chain, using a new tactic, the "shop-in." The company signed an agreement. Then a series of picket lines at San Francisco's Sheraton-Palace Hotel, marked by over 120 arrests (about half of them U.C. students), culminated on March 8 in a picket line of 2000 and a lobby sit-in. Of the 767 demonstrators arrested for blocking the lobby, 100 were U.C. students. The Hotel Owners' Association signed an agreement. Later the same month, anti-discrimination picketing began at the city Cadillac agency (100 arrests, about 20 from U.C.) and eventually spread to other Auto Row agencies (another 226 arrests). The courts were jammed with cases; some got jail sentences and fines. In June, Campus CORE sponsored a sit- in at the U.S. District Attorney's office to dramatize federal inaction on the Mississippi murders, and the demonstrators were forcibly carried out. Bay Area CORE started preparing for an assault even on the octopodous Bank of America.

Then, on September 4, the Ad Hoc Committee launched a picket line against one of the biggest dragons of all, the Oakland Tribune, run by William Knowland, Goldwater's state manager, a kingpin in the entire power structure of the East Bay, especially Alameda County (which includes Berkeley).

It was clearly inevitable that a civil-rights movement which sought to erase all discrimination in hiring would come squarely up against the power structure of the Bay Area. Of the various civil-rights groups in the area, only Campus CORE and Friends of SNCC were university clubs, but a big action, especially if it were militant, could count on a good part of the "troops" coming from the the campus.

That summer, the picture was complicated by another factor. The Republican convention was going to meet in San Francisco: Goldwater versus the "moderates" Lodge, Scranton and Rockefeller. For the first time within man's memory, the Berkeley campus became a hotbed of political activity not only by radicals but also by conservative students. Supporters of the various GOP contenders began to organize for work at the convention. Campus CORE also organized an anti-Goldwater demonstration at the Cow Palace.

Some time in July, a reporter for the Oakland Tribune (which was boosting Goldwater, of course) noted that pro-Scranton students were recruiting convention workers at a table placed at the Bancroft entrance to the campus, the then-regular place for this type of activity. It appears that he, or someone else from the Tribune, pointed out to the administration that the table was on university property and violated its rules. An official report by Chancellor Strong ** later admitted that "The situation [regarding political activity at Bancroft] was brought to a head by the multiplied activity incidental to the primary election, the Republican convention, and the forthcoming fall elections," and that administration officials began taking up the question on July 22 and 29.

But Strong himself was out of town till early August and nothing was done. Then on September 2 the Ad Hoc Committee announced it would picket the Oakland Tribune. On the 3rd the Tribune appeared with a front-page "Statement" personally signed by William Knowland, denouncing the move. On the 4th, the picketing started. The same day the Berkeley administration again took up the question of campus political activity, for the first time since July 29 (according to the dates given in Strong's report).

Flat statements that the crisis was originally touched off by Goldwaterite complaints against pro-Scranton recruitment appeared later both in the Hearst daily, the S. F. Examiner, of December 4, and in the S. F. Chroniclc of October 3 and December 4. Two affidavits by students were later sworn out stating that, in September, Chancellor Strong told a number of people at a campus meeting that the Oakland Tribune had phoned him to ask whether he was aware that the Tribune picketing was being organized on university property, i.e., at the Bancroft entrance.

According to this account, then, it was the Goldwaterite forces of Knowland's Tribune who put the administration on the spot with respect to the toleration of political activities at the Bancroft sidewalk strip. Strong's official report admits that some, though not all, of the campus officers did know right along that this strip was university property, not city property, but that up to this time they "considered no acts to be necessary."

Now action was demanded. Knowland, who was not much of an idealist but was very much of a Power, was on the administration's neck, and something had to be done. An extra urgency was added by the fact that the university was very anxious that a bond issue (Proposition 2) be passed at the November 3 election; it wanted no anti-university publicity which might turn votes against it, let alone a press campaign led by the Tribune.

The outside pressures were mounting. Many believe that the Bank of America also had a hand in the pressure, but the bank's president, Jesse Tapp, was also one of the most important members of the Board of Regents, and any pressure he chose to apply or amplify need not have been exerted from the outside.

One of the most unique features of the Berkeley student revolt is that from its beginning to its climax it was linked closely to the social and political issues and forces of the bigger society outside the campus. At every step the threads ran plainly to every facet of the social system: there were overt roles played by big business, politicians, government leaders, labor, the press, etc. as well as the Academy itself. This was no conflict in the cloister.

* Throughout this account, "free speech" (in quotation marks) is used as a shorthand term for the range of student demands on freedom of political activity and social action, as well as free speech in the narrow sense.

** His report (mimeo.) to the Academic Senate, dated October 26, 1964.

6

The Administration Clamps Off the Safety Valve

The Bancroft sidewalk strip became the first battleground because the administration had designedly left this small area as the sole safety valve for much of student political activity. The explosive forces become concentrated there.

Traditionally the "free speech" arena at Berkeley used to be at Sather Gate, but in 1959 the block between the gate and Bancroft Avenue was turned into a plaza connecting the new Student Union on one side with Sproul Hall (the administration center) on the other. This plaza, called Sproul Hall Plaza (or Upper Plaza), is going to figure as the next battleground of our story; at this point it had definitely become a part of the campus.

The Bancroft Avenue sidewalk, just outside, had been regarded as city property, not under the jurisdiction of the university. Hence all the activities which the "Kerr Directives" had banned from campus could find an outlet only here. Here clubs set up folding card tables, displaying their literature or other publications, collecting funds, and selling bumper strips or buttons and such. Here students might stop to talk with the "table-manners" (who are not to be confused with Emily Post's subject). In this way tables were used to "recruit" pro-Scranton students for the Republican convention, or to "recruit" for CORE civil-rights actions.

But in fact the Bancroft sidewalk was not all city property. A line marked by plaques separated it into a 26-foot university strip running along the campus and a smaller city strip running along the curb. As mentioned, the administration always acted as if it were all the city's; as late as the spring of 1964, the dean's office was directing clubs to get city permits to set up their tables.

To be sure, the administration had in 1962 formally set up an official "Hyde Park" (free speech) area on campus, in the Lower Plaza. It was out of sight of the main line of student rafflc in and out of the campus, and, the students felt, this was why the administration found it suitable for the purpose. By the same token, the students generally ignored it, and it was largely unused. The de facto "Hyde Park" was the Bancroft sidewalk.

Then on September 14 the dean's office announced that even this safety-valve area was going to be closed: tables and their activities were banned. They had fired on Fort Sumter.

It must be said for Dean of Students Katherine Towle that she did not conceal the basic motivation. Speaking to protesting club representatives in the following week, she openly referred to the "outside pressures." Also, the Daily Cal reported on September 22:

... Dean Towle admitted [Sept. 21] that the question came up in the first place because of the frequent announcement of and recruitment for picket lines and demonstrations going on in the area in the past.

But this was not so much an "admission" as it was an appeal or plea: Please understand our problem with these outside pressures, and don't push us too hard.

What was supposed to happen from here on was pretty much cut-and-dried: The students would protest bitterly; the administration would explain that rules-were-rules-and-it-had-no-alternative; perhaps some minor concessions would be made; the protests would peter out; and the new setup would be an accomplished fact by the time the students had settled into their new classes for the semester.

President Kerr had articulated this somewhat bored view of student protests in a passage of his 1963 Godkin Lectures which was eliminated from the text when they were published as The Uses of the University:

One of the most distressful tasks of a university president is to pretend that the protest and outrage of each new generation of undergraduates is really fresh and meaningful. In fact, it is one of the most predictable controversies that we know -- the participants go through a ritual of hackneyed complaints almost as ancient as academe, believing that what is said is radical and new.

The following January, Kerr was going to tell newsmen: "They took us completely by surprise." Something went wrong with the predictability of the hackneyed complaints. Instead there was a "protest and outrage" that was "fresh and meaningful" and therefore even more distressful to the president.

7

"What's Intellectual About Collecting Money?"

When Kerr finally gave the public his history of how the fight all started (interview of January 5), his account went as follows:

Returning from a trip abroad on September 15, he found that, the day before, the Berkeley administration had closed the Bancroft political arena. He thought this was a mistake, but, instead of correcting the mistake, he suggested that Sproul Hall steps be made a "Hyde Park" area. "I thought," he said, "we could get things back into channels of discussion if we showed reasonableness, but it didn't work." The interview adds: "Instead of reasonable discussion Kerr got the Free Speech Movement."

We shall see the administration's view of reasonable discussion.

The edict of September 14 was handed down, a week before classes started, with no consultation of the student clubs -affected. There was likewise none even with the ASUC, the "sandbox" student government. The administration ignored the impotent ASUC as fully as did the student protesters.

"Off-campus politics will be removed from its last on-campus stronghold," interpreted the Daily Cal. "The boom has been lowered ... on off-campus political activities within the limits of the Berkeley campus,' reported the Berkeley Daily Gazette.

In addition to banning the use of tables (and posters) at Bancroft, the September 14 announcement also specifically prohibited fund-raising, membership recruitment and speeches, and the "planning and implementing of off-campus political and social action." The reason given for banning the tables was their "interference with the flow of traffic." The clubs offered to conduct a traffic-flow survey, but without result.

The ban on the activities was based on Art. 9, Sec. 9 of the State Constitution which reads: "The University shall be entirely independent of all political or sectarian influence and kept free therefrom in the appointment of its regents and in the administration of its affairs ..." Many pointed out in the ensuing three months that the- best way to insure the university's independence of "political or sectarian influence" was to permit free speech and advocacy of all views on campus, not to bar any.*

Although the September 14 regulations were presented as the "historic policy" of the university -- historically winked at -- a second and new version of the "historic policy" was disclosed a week later, on September 21, after student protests spread. Following a conference with Kerr and Strong, Dean Towle met a group of club representatives and announced some "clarifications":

(1) Sproul Hall steps would be the new "Hyde Park" -- the concession suggested by Kerr -- but no voice amplification would be allowed. (2) A number of tables would be allowed at Bancroft; presumably it had been ascertained in the meantime that they would not block traffic. (3) But at the tables there could still be no fund-raising, no recruitment, and no advocacy of partisan positions. Only "informative" material, not "advocative" "persuasive," could be distributed for or against a candidate, a proposition or an issue; but no urging of "a specific vote" or "call for direct social or political action." Chancellor Strong added: there could be no "mounting of social and political actions directed to the surrounding community."

The student representatives tried to find out where the line was being drawn between informing and advocating, and ran into the Semantic Barrier. The dean offered the interpretation that "information" about a scheduled picket line would be considered "advocacy."

This abstruse distinction between "information" and "advocacy" had to be partially scuttled within the week, after a discussion on September 24-25 between the campus officers and Kerr. The third version of the "historic policy" was announced on September 28 by Chancellor Strong. "Advocacy" would be permitted of a candidate or a proposition currently on the ballot, but that was all.

And the chancellor announced at the same time that discussion on the matter was over: "no further changes are envisaged. The matter is closed." So much for "reasonable discussion." **

By this time it was quite clear that the administration could not possibly believe it was merely enforcing the state constitution. It would have been difficult to claim that the constitution smiled on advocacy of Goldwater after he had become the candidate but frowned on advocacy of Scranton before a candidate had been chosen. Nor would a battery of lawyers have undertaken to prove that it was the constitution that banned "information" about a scheduled picket line. Nor could the constitution explain why fund-raising on campus was allowed for the World University Service, for schools in Asia, while SNCC was barred from collecting for "freedom schools" in Mississippi, or CORE for tutorials in Oakland.

But these interpretations had the undeniable virtue of giving the "outside pressures" what they were demanding. At the same time the new version eased an embarrassing contradiction: the university was spending taxpayers' money to mail out propaganda in favor of Proposition 2 (the bond issue) while it cracked down on students for collecting nickels for "No on Proposition 14" (the anti-fair-housing measure). It had taken two weeks and Kerr's best advice to work out this highly selective gloss on the state constitution, which would give substance to Power and rhetoric to Ideals.

(Version 4 of the "historic policy" was going to come in November. )

Students and some faculty members reacted sharply on educational grounds to the prohibition of "mounting social and political action." A statement by the clubs, for example, spoke of an "obligation to be informed participants in our society -- and not armchair intellectuals." Kerr took up another challenge:

In an apparent retort to the history professors who joined the student protests on the Berkeley campus earlier this week, Kerr said: "If action were necessary for intellectual experience we wouldn't teach history, since we cannot be involved with the Greeks and Romans." (S.F. Chronicle, Sept. 27.)

Since we cannot learn through acting in Greek history, is it proper for an educational institution to discourage acting in our own history? The implied argument did nothing to improve the intellectual respectability of the administration's stand in the eyes of the university community. It did not help that Kerr also added: "What's so intellectual about collecting money?" Only the civil-rights workers in Mississippi could have replied adequately.

* Even Kerr later admitted that "by the fall of 1964, certain of the university's rules had become of doubtful legal enforce ability." (Calif. Monthly, February 1965, p. 96.)

** Three days later, a statement by the chancellor asserted that the new policy "is now and has always been the unchanged policy of the university.... No instance of a newly imposed restriction or curtailment of freedom of speech on campus can be truthfully alleged for the simple reason that none exists."

8

The Clubs Fight Back

The "off-campus" clubs formed a United Front on September 17 to protest the new rules. It consisted of some 20 organizations: civil-rights groups, radical and socialist groups, religious and peace groups, Young Democrats, and all three Republican clubs (including Youth for Goldwater) plus another right-wing conservative society. The conservatives' campus publication Man and State later summarized:

The new regulations were immediately opposed by all campus political organizations.... The initial conversations with the administration left no doubt but that the regulations were a result of outside pressure and were intended to stop any political activity on campus.... The negotiations failed.

Right across the political board from left to right, not one of the clubs felt that the administration was set on "reasonable discussion."

Next day, the United Front submitted a request to the dean for restoration of the tables, agreeing to a number of conditions regulating their use. On the first day of classes, September 21, Dean Towle met with them and unleashed Version 2 of the regulations. The student representatives thanked her for the improvement and replied that it was not enough. By noon that day the first protest demonstration unrolled before Sproul Hall: a picket line of 200 carrying signs such as "Bomb the Ban" and "UC Manufactures Safe Minds."

The most surprising aspect of yesterday's picketing was the relatively large numbers of non-activists who joined the picket line, took a few turns in front of Sproul, and then turned their sign over to others. (Daily Cal, Sept. 22.)

In addition, tables were set up (with permits) but proceeded: to offer "advocative" material in defiance of the order. All the clubs had agreed on the previous evening that no one of them would move its table to the city-owned strip -- now labeled the "fink area." Even the conservatives agreed on this measure of solidarity, though not on setting up tables in violation of the rules. A Daily Cal editorial warned, "Campus administrators are making a mistake," though it urged moderation in protest. The next day even the ASUC Senate addressed a request to the Regents "to allow free political and social action," etc.

On the night of the 23rd there was a "Free Speech Vigil" on Sproul Hall steps, beginning 9 P.M. -- about three hundred strong. In response to a report that Kerr and the Regents were meeting at University House, the group decided, after a quarter-hour discussion and a vote, to march there, walk around for five minutes and leave. "The single-file procession stretched a quarter mile, and was called remarkable for-its orderliness," reported the Daily Cal. (This note, surprise at the self-disciplined orderliness, was to be struck by all unbiased observers from here on. ) All Regents having left, except the secretary, a letter of appeal to the board was composed and left. Back at Sproul Hall, some 75 students composed themselves till morning, when they greeted the arrivals with singing.

On September 28 the United Front opened the throttle a little more. "Advocative" tables were set up at Sather Gate itself, since the new rules were supposed to be campus-wide now. At 11 A.M. Chancellor Strong was scheduled to open an official university meeting to present awards, in the Lower Plaza. The United Front held a rally in Dwinelle Plaza to group its forces, and then marched as a picket line to the chancellor's meeting (where, incidentally, Strong unexpectedly announced Version 3 of the rules). Against the instructions of one of the deans, the picket line went down the aisles as well as around the perimeter.

It was a strange scene: there were at least 1000 picketers -- 1500 according to one paper -- and there were probably not quite that many students attending the official meeting. Two of the student leaders, including Mario Savio of SNCC, were threatened with disciplinary action; some of the clubs were given warnings.

On September 29 the dean's staff began making hourly checks of violations, and at first found the students "cooperative," with the exception of one Slate student. In the afternoon SNCC set up a table in violation of the rules.

9

The First Sit-in and the Eight Suspensions

On Wednesday, September 30, the dean's checks continued, but this time they ran into a stiffening resistance. By afternoon five students -- Brian Turner, Donald Hatch, David Goines, Elizabeth Stapleton and Mark Bravo -- who had refused to back down on what they insisted were their constitutional rights, were summoned to the dean's office 3 o'clock. The deans quit taking names when they realized that their list might run into hundreds. Hastily written petitions were circulated among the students gathered in the Sather Gate area, and some 400 of them signed statements on the spot, like the following:

We the undersigned have jointly manned tables at Sather Gate -- realizing that we were in violation of University edicts to the contrary, and that we may be subject to expulsion.

At 3 o'clock over 500 students showed up at the dean's office together with the five cited. Their spokesman was Mario Savio, not one of the five. He told the dean: all the students present had equally violated the rules; they wanted equal disciplinary treatment and were not going to leave till assured of it.

... the administration explained that it was punishing only observed offenses, an explanation which under the circu stances struck the student community as disingenuous ... (Suggestion for Dismissal, p. 5.) *

Right there, instead, three more students were added to the cited list -- Mario Savio, Art Goldberg and Sandor Fuchs -- making eight in all. Originally scheduled for 4 P.M. had been another meeting between the administrators and the club representatives; but this point the administration unilaterally canceled the parley on the ground that "the environment was not conducive to reasonable discussion." Did the chancellor consider that I his own intimidation campaign of the past two days, preceding | this scheduled meeting, had been "conducive to reasonable discussion?" At any rate, the students were inaugurating a principle they never dropped: When they try to pick off a few leaders, hit 'em with all you've got. As Kerr was later to write retrospectively about the FSM activists: "They have a remarkable sense of solidarity among themselves ..."

The students, swelling eventually to several hundreds, stayed in the halls and turned the sit-in into a mass "sleep-in," till early morning. Shortly before midnight, after conferring with Kerr, Chancellor Strong issued a statement announcing that the penalty of "indefinite suspension" was being assessed against the eight students.

It was characteristic of the panicky virulence with which Strong and Kerr moved to strike that they fixed on a penalty which did not even exist in the very university regulations which they were presumably defending. But this was only one detail. For an assessment of this fateful decision which was made by the chancellor in conference with the president, we must look ahead to the judgment finally rendered in mid-November by a faculty committee appointed by the Academic Senate, usually called the Heyman Committee after its chairman, a professor of law:

The procedures followed were unusual. Normally, penalties of any consequences are imposed only after hearings before the Faculty Student Conduct Committee. Such procedure was not followed here with the result that the students were suspended without a hearing ... in hindsight, it would have been more fitting to announce that the students were to be proceeded against before the Faculty Committee rather than levying summary punishments of such severity. We were left with the impression that some or all of these eight students were gratuitously singled out for heavy penalties summarily imposed in the hope that by making examples of these students, the University could end the sit-in and perhaps forestall further mass demonstrations.

In the case of six students out of the eight, even the administration admitted to the Heyman Committee that the table-manning offenses would normally have been considered "innocuous" but that the draconic penalty was imposed for the "context." The Heyman Committee disagreed, since it saw the context as a sincere belief by the students that their constitutional rights were at stake:

Moreover, we believe [went on the Committee] that these students viewed their actions in operating the tables as necessary to precipitate a test of the validity of the regulations in some arena outside the University ... [the Chancellor had] made it clear that the President and the Regents had rejected in final form the request of the ASUC Senate for changes in the rules to permit solicitation of funds and membership and organization of political and social action campaigns on campus. The door was thus seemingly closed to any negotiations on these central points.

We should note two things in connection with this very important passage. (1) Later on, the ASUC Senate was going to decide, unanimously, to force a court test of the regulations through an arranged violation of them -- that is, it decided do exactly what the rebel students were suspended for doing. (2) The last two sentences give an official quietus to Kerr's later claim that all he wanted was "reasonable discussion." At every crucial point the administration systematically struck the attitude "Not negotiable!" **

This persistent intransigence made sense in terms of the usual bureaucratic calculation: insofar as the students could be induced to give up all hope of moving the administration, they could the more easily be discouraged from even making the attempt. It is a usually effective approach; the only reason it failed in this case is that the administration confronted a student leadership which was not ruled by "possibilism." This indeed was going to be the FSM's main offense in the eyes of a number of dogmatically "possibilist" academics, who were going to "project" the Administration's indubitable intransigence onto the militant students.

Regarding the sit-in at the dean's office, the Heyman Committee observed as follows, naturally unaware of the full future import of its remarks:

In retrospect, the University's best tactic might have bees to carry on operations in Sproul Hall as usual, leaving the students where they were until the demonstration ended naturally through the weariness of the demonstrators.

And here is its general summary on the suspensions:

... the procedure by which the University acted to punish these wrongdoings is subject to serious criticism. The relevant factors are: first, the vagueness of many of the relevant regulations, second, the precipitate action taken in suspending the students some time between dinner time and the issuance of the press release at 11:45 P.M.; third, the disregard of the usual channel of hearings for student offenses -- notably hearings by the Faculty Committee on Student Conduct; fourth, the deliberate singling out of these students (almost as hostages) for punishment despite evidence that in almost every case others were or could have been easily identified as performing similar acts, and fifth, the choice of an extraordinary and novel penalty -- "indefinite suspension" -- which is nowhere made explicit in the regulations, and the failure to reinstate the students temporarily pending actions taken on the recommendations of this committee. [The last remark is ahead of our story.]

"We do not believe or suggest that the administration was motivated by malice or vengeance," the Committee assures us, expressing "confident faith that the university administration will be as desirous as we are of correcting [the shortcomings]." Alas, chancellor, president and Regents were going to reject the Heyman Committee's recommendations about as summarily as the eight students had been suspended.

The administration does not always act so precipitately in putting regulations into force. For example, in connection with its laudable decision to abolish racial discrimination in fraternities, the administration gave frets a period of five years to get into line. The long delay may have been justifiable; it is the contrast that tells the story.

* Even Kerr later admitted that "by the fall of 1964, certain of the university's rules had become of doubtful legal enforce ability." (Calif. Monthly, February 1965, p. 96.)

**Cf. the later summary statement by Chancellor Strong: "During the days leading up to the fateful evening of October 2, the position was stated and restated for all to hear that the university would never negotiate with individuals who were at time engaged in unlawful behavior ..." (Confidential report to Regents dated December 16, 1964. Published in S.F. Examiner, March 13, 1965.)

10

A Couple of Rebels

For each student involved, this last week in September was also a personal crisis.

For example, there was Brian Turner, l9-year-old sophomore in economics, who had joined SNCC little more than a reek before. On the 29th the 'little deans" had approached him, as others, and asked if he knew he was breaking the rules.

"1 backed down on Tuesday because I didn't want to go alone," he said. "I folded up the table and went home. But I thought about it overnight and I went back. When they came up to see me again, my own principles prevented me from leaving. I had decided that the freedom of 27,000 people to speak freely is worth the sacrifice of my own academic career at Cal." (S. F. Chronicle, Oct. 3.)

Turner's background was only mildly liberal (and in fact he was going to become one of the "moderates" in the FSM spectrum) but in one short week he had to educate himself fast on the most fundamental characterological question in politics: In confrontation with oppressive Power, do you adapt discreetly or do you go over into opposition?

Mario Savio, a junior, who had become the spokesman of the group on September 30; was a different case: he already knew who he was. This was perhaps his main title to the mantle of leadership which did in fact fall on him.

Not a glib orator, retaining remnants of a stutter, rather tending to a certain shyness, he yet projected forcefulness and decision in action. This was the outward glow of the inner fact that he was not In Hiding -- he was in open opposition, and he had no doubts about it. He became the recognized leader of the FSM not in a contest but mainly because there was no other eligible student around who was morally as ready and capable of assuming the burden.

Still under 22 when the fight broke out, Mario Savio had been a high-grade student in three colleges: Manhattan College (Catholic), Queens College (New York City), and Berkeley. He had moved from absorption in physics and mathematics to a major in philosophy. He had spent his summer in 1963 on a do-gooder project in Taxco, Mexico; then in the summer of 1964 he became a SNCC voter-registration worker in Mississippi. He saw a co-worker beaten. Most important, he saw Mississippi, where the relationships between Ideals and Power quiver out in the open like exposed nerve endings.

When at summer's end he returned to Berkeley, from a state where Law and Order meant the legally organized subjection of a whole people, the administration greeted him with the news that Law and Order meant he could not even collect quarters to aid those people. He knew all about this kind of Law and Order.

Note to readers:

We are looking for volunteers to help us scanning and proofreading the rest of

Hal Draper's book as well as many other documents in our archives. If you'd like to help (and you don't need to be in Berkeley to do this) please email us about what you might do.URL of this page: http://www.fsm-a.org/draper/draper_ch1-10.html

Last revision: September 16, 2001