An article about Mario Savio appeared in the February 16, 1965

issue of Life Magazine

Below is the text of the article.

HERE is a PDF of the actual article

including the cover of that issue.

Life Magazine

02/26/1965 pages 100-101

EDUCATION

ANGRY WORDS FROM MARIO SAVIO, SPOKESMAN FOR CALIFORNIA'S STUDENTS NOW FACING

TRIAL

‘The university has become a factory’

from an interview - by Jack Fincher

In what may be the largest court test in the history of American jurisprudence, 703 demonstrators arrested during last fall's sit-in at the University of California at Berkeley will be set for trial in Municipal Court this week. The defendants, most of them students, are charged with trespassing, resisting arrest and unlawful assembly.

The direct cause of the sit-in, which climaxed weeks of demonstrations, was a

sudden tightening up of the rules governing recruiting and fund raising for

off-campus political and civil rights causes. University officials soon realized

this was an arbitrary and unwise move and modified the regulations. But by then

the episode had brought into the open an enormous, smoldering frustration on the

part of many who feel the very size and impersonality of their university is

depriving them of a worthwhile education. These dissidents soon organized as the

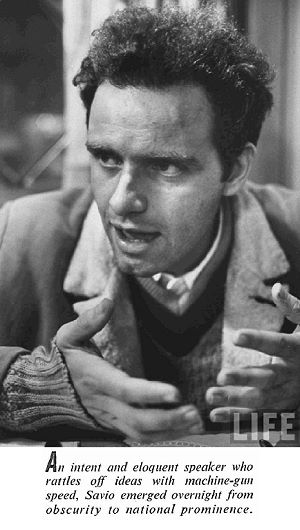

Free Speech Movement and found an eloquent spokesman in 22-year-old philosophy

major Mario Savio, a native of New York. His own views—excerpted here from a

lengthy interview with Life's correspondent in San Francisco, Jack Fincher—cut

to the heart of a system he sees as "totally dehumanized, totally

impersonalized, created by a society which is wholly acquisitive." Savio's

rebellion is not so much political as against schools—and a society—where

everything seems to be geared to "performance and award, prize and

punishment—never to study for itself." Because Savio's outlook is shared by so

many, its significance goes far beyond the court trial he and his contemporaries

will face this week.

**********

THE ROOTS OF THE PROBLEM

'The thing's turned on its head. Those who should give orders—the faculty and

students—take orders, and those who should tend to keeping the sidewalks clean,

to seeing that we have enough classrooms—the administrators—give the orders....

As [social critic] Paul Goodman says, students are the exploited class in

America, subjected to all the techniques of factory methods: tight scheduling,

speedups, rules of conduct they're expected to obey with little or no say-so. At

Cal you're little more than an IBM card. For efficiency's sake, education is

organized along quantifiable lines. One hundred and 20 units make a bachelor's

degree.... The understanding, interest and care required to have a good

undergraduate school are completely alien to the spirit of the system....

The university is a vast public utility which turns out future workers in today's vineyard, the military-industrial complex. They've got to be processed in the most efficient way to see to it that they have the fewest dissenting opinions, that they have just those characteristics which are wholly incompatible with being an intellectual. This is a real internal psychological contradiction. People have to suppress the very questions which reading books raises.'

ON HIMSELF

I am not a political person. My involvement in the Free Speech Movement is

religious and moral.... I don't know what made me get up and give that first

speech. I only know I had to. What was it Kierkegaard said about free acts?

They're the ones that, looking back, you realize you couldn't help doing.'

ON THE ADMINISTRATION

[President] Clark Kerr is the ideologist for a kund of "brave new world"

conception of education. He replaces the word "university" with "multiversity."

The multiversity serves many publics at once, her says. But Kerr's publics...is

the corporate establishment of California, plus a lot of national firms, the

government, especially the Pentagon. It's no longer a question of a community of

students and scholars, of independent, objective research, but rather of

contracted research, the results of which are to be used as those who contract

for it see fit.... Why should the business community...dominate the board of

regents? The business of the university is teaching and learning. Only people

engaged in it—the students and teachers—are competent to decide how it should be

done.

ON BEING AN AMERICAN STUDENT

America may be the most poverty-stricken country in the world. Not materially.

But intellectually it is bankrupt. And morally it is poverty-stricken. But in

such a way that it's not clear to you that you're poor. It's very hard to know

you're poor if you're eating well.

In the Berkeley ghetto—which is, let's say, the campus and the surrounding five or six blocks—you bear certain stigmas. They're not the color of your skin, for the most part, but the fact that you're an intellectual, and perhaps a moral nonconformist. You question the mores and morals and institutions of society seriously; you take serious questions seriously. This creates a feeling of mutuality, of real community. Students are excited about political ideas. They're not yet inured to the apolitical society they're going to enter. But being interested in ideas means you have no use in American society . . . unless they are ideas which are useful to the military-industrial complex. That means there's no connection between what you're doing and the world you're about to enter.

There's a lot of aimlessness in the ghetto, a lot of restlessness. Some people are 40 years old and they're still members. They're student mentalities who never grew up: they're people who were active in radical: politics, let's say, in the Thirties, people who have never connected with the world, have not been able to make it in America. You can see the similarity between this and the Harlem situation.

ON THE STUDENT PROTESTS

At first we didn't understand what the issues were. But as discussion went on,

they became clear. The university wanted to regulate the content of our speech.

The issue of the multiversity and the issue of free speech can't be separated.

There was and is a need for the students to express their resentment . . .

against having to submit to the administration's arbitrary exercise of power.

This is itself connected with the notion of the multiversity as a factory.

Factories are run in authoritarian fashion—non-union factories, anyway—and

that's the nearest parallel to the university. . . . The same arbitrary attitude

was manifest when they suddenly changed the political activities rules.

As for ideology, the Free Speech Movement has always had an ideology of its own. Call it essentially anti-liberal. By that I mean it is anti a certain style of politics prevalent in the United States: politics by compromise—which succeeds if you don't state any issues. You don't state issues, so you can't be attacked from any side. You learn how to say platitudinous things without committing yourself, in the hope that somehow, that way, you won't disturb the great American consensus and somehow people will be persuaded to do things that aren't half bad. You just sort of muddle through. By contrast our ideology is issue-oriented. We thought the administration was doing bad things and we said so. Some people on the faculty repeatedly told us we couldn't say or do things too provocative or we'd turn people off—alienate the faculty. Yet, with every provocative thing we did, more faculty members came to our aid. And when the apocalypse came, over 800 of them were with us.

ON THE TEACHING SITUATION

They should supply us with more teachers and give them conditions under which

they could teach—so they wouldn't have to be producing nonsensical publications

for journals, things that should never have been written and won't be read. We

have some magnificent names, all those Nobel Prize winners. Maybe a couple of

times during the undergraduate years you see them 100 feet away at the front of

a lecture hall in which 500 people are sitting. If you look carefully, if you

bring along your opera glasses, you can see that famous profile, that great

fellow. Well, yes, he gives you something that is uniquely his, but it's

difficult to ask questions. It's got to be a dialogue, getting an education.

The primary concern of most of the teaching assistants is getting their doctorates. They're constantly involved in their own research, working their way into so narrow a corner of their own specialty that they haven't the breadth of experience or time to do an adequate job of teaching. Furthermore, what they've got to do, really, is explain what the master told you, so you can prepare to take his tests. When teaching assistants deviate from the lesson plans to bring in new material, this enriches their students; but sometimes another result is to make it more difficult for those students to do well on the exams.

ON CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE

If you accept that societies can be run by rules, as I do, then you necessarily

accept as a consequence that you can't disobey the rules every time you

disapprove. That would be saying that the rules are valid only when they

coincide with your conscience, which is to insist that only your conscience has

any validity in the matter. However, when you're considering something that

constitutes an extreme abridgment of your rights, conscience is the court of

last resort. Then you've got to decide whether this is one of the things which,

although you disagree, you can live with. Only you can decide; it's openly a

personal decision. Hopefully, in a good society this kind of decision wouldn't

have to be made very often, if at all. But we don't have a good society. We have

a very bad society. We have a society which has many social evils, not the least

of which is the fantastic presumption in a lot of people's minds that naturally

decisions which are in accord with the rules must be right—an assumption which

is not founded on any legitimate philosophical principle. In our society,

precisely because of the great distortions and injustices which exist, I would

hope that civil disobedience becomes more prevalent than it is.

Unjustified civil disobedience you must oppose. But if there's a lot of civil disobedience occurring, you better make sure it's not justified.

ON THE TRIAL

They can only try us in several ways—a mass trial, a group trial, individual

trials, or some combination. None or these four ways can give US due process.

Even individual trials would be held before different judges and juries. In

earlier civil rights cases here, we've had different verdicts handed down for

the same offense.

Some people say, "Okay, they've been crying for their political acts to be judged only by competent authorities—the courts, not the university; so now they get what they want and they aren't happy." That isn't the point. We're not complaining about being treated fairly by the courts. We're complaining precisely because we're not going to be treated fairly, because we're not going to get due process. I didn't commit myself to accept whatever the state might do to me, you know, and I'm not going to accept anything which doesn't guarantee me my constitutional rights through fair trial. 1 think it's a scandal that an action which can be argued legitimately as an exercise of constitutional rights may be punished so severely that people who have taken part in it—and others to whom it has been an example—may be thereafter dissuaded from exercising their constitutional rights.

(Thanks to FSM Bibliographer, Barbara Stack, for the work on this.)