FSM Vets' News & Views

JACK WEINBERG STILL FIGHTS THE GOOD FIGHT TO KEEP ENVIRONMENTALISM FROM FADING AWAY

By Connie Lauerman, Tribune Staff Writer - April 21, 2000

As a student activist in the turbulent '60s, Jack Weinberg was arrested several times.

He was nabbed during civil rights demonstrations in the South and during a campaign by Berkeley students to secure jobs for minorities in San Francisco hotels.

It happened again while he was passing out leaflets on matters such as civil rights, nuclear testing, the Vietnam War and apartheid, after the university had banned such activities on campus. The ban gave birth to the Free Speech Movement, a high point of dissent in the '60s at Berkeley.

Now an environmentalist, Weinberg was arrested last month in Manila. He was one of 26 Greenpeace activists detained after they delivered a container of poisonous chemical waste to the U.S. Embassy. The toxins (PCBs) came from a residential area near a former U.S. military base.

Talking about the experience 10 days later in Chicago, where he lives, Weinberg, gray-haired and bespectacled, seemed a bit bemused.

"They hauled us off very gingerly," he said. "They ended up not charging us. Greenpeace has a high profile, and I had some concerns [the authorities] would get nasty about it, and I'd be deported.

"I want to keep going back. I have work I want to keep going. But you have to do something to make your point."

Unlike some of his radical compatriots from the 1960s, Weinberg has neither burned out nor faded away. His fervor has crystallized in a global take on environmental protection.

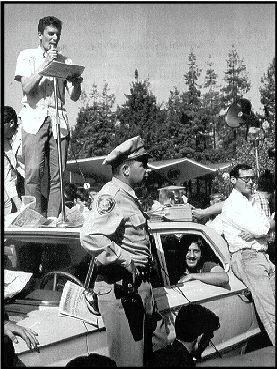

Photo of Jack in the police car 1964

photo ©1964 Howard HarawitzPat Costner, of Eureka Springs, Ark., senior scientist for Greenpeace International, has been working with

Weinberg on environmental issues for a decade. "He is one of my favorite people," she said. "He has a

wonderful combination of vision and practicality from the policy perspective."And he understands the art of compromise and is very skillful in being able to reframe controversial or

problematical issues with the outcome of getting broader agreement, if not consensus."He recently turned 60 and found it "a bit of a gas." As well he should. He was, after all, the young man who was credited with saying: "Don't trust anyone over 30." His off-the-cuff remark to a San Francisco newspaper reporter covering the Berkeley student protest movement was picked up by other journalists and seized by the leaders of the movement once they saw how much it riled their elders.

"The fact that I've been able to stay engaged all this time, I feel, is an accomplishment," said Weinberg, a native of Buffalo.

It would seem that for many others, interest in environmental protection peaked years ago. What else explains the popularity of polluting sport-utility vehicles, rampant consumerism, sprawling development and other assaults to the planet?

"Part of the problem is that there is a perception out there, with a lot of public relations money behind it, that things are getting better," Weinberg said. "Some things are getting better. There's more control of gross

discharges into lakes, rivers and streams, although they're not pristine."You remember what air used to be like in America? The air is not perfect, but the fact is you don't taste and smell the air every second here."

What has gotten worse, Weinberg said, is "the destruction of biodiversity. Neither here nor anywhere else in the world do I see good, rational, long-term land use planning."

Weinberg's issue of choice has been the environment since 1977, when the Northern Indiana power company announced the construction of a nuclear power plant on the shore of Lake Michigan about five miles from his home in Gary, where he was working in a steel mill.

He had dropped out of graduate school, where he was studying math, to concentrate on civil rights work. By 1969, he decided societal change could not be realized solely through activists "concentrated in elite universities" without a component in blue-collar America. So he moved to Detroit to work in an auto plant, where he was an active union member and not involved in the first Earth Day in 1970 (the 30th anniversary of the event will be celebrated Saturday).

It took an economic downturn and a move to Gary to work for U.S. Steel before his environmental activism flowered.

Weinberg said manual labor (he worked as a metallurgical tester at U.S. Steel) was easy for him, mostly because he didn't have to spend his free time thinking about work. So it was perfect to support his main activity--fighting nuclear power plants.

"In the late '70s, I had an epiphany that changed my way of thinking," he said. "It became clear to me that we could degrade the Earth to a point where it could no longer support human populations."

He got to know people in the national environmental movement, particularly Barry Commoner, who visited Gary several times to aid in the fight against the proposed Bailey Nuclear One power plant.

Commoner made an ill-fated bid for president in 1980 under the Citizen Party banner, and Weinberg organized the Indiana Citizen Party to put him on the ballot.

After the successful, five-year battle against the Bailey nuclear plant, Weinberg served on the boards of a number of environmental groups, including the Indiana Dunes Council, the Indiana Citizens Action Coalition

and the Lake Michigan Federation.Although he said his youthful notion of effecting change by involving conservative blue-collar workers "was partly romantic," Weinberg said the experience was "invaluable" and "grounding." Wanting to preserve the Earth, he said, "is something that everybody has in common. Even if you're the richest, most powerful man in the world, you still have no interest in degrading the life possibilities of your grandkids."

When another economic downturn cost Weinberg his steel job in 1984, he moved to Chicago, working in a string of jobs, including one in a printing plant. He remained active in environmental activities in his spare time.

Yet he said he felt "fairly alienated" and dissatisfied with local efforts to solve problems he viewed in a global context.

He was revitalized in 1989 when he took a full-time professional job with Greenpeace International, coordinating its Great Lakes project. Gross

pollution--uncontrolled discharges of grease, oil, sewage, phosphates and such into lakes and rivers--was stopping, but fish and birds were not coming back. The problem, Weinberg said, was manmade chemicals, called "persistent toxic substances," that had worked all the way up the wildlife food chain.As a result, Great Lakes fish had abnormal thyroid glands, and birds had deformed beaks and behavioral problems.

"Some birds that could actually hatch eggs then didn't know how to raise their young and the young would die," Weinberg said. "You also had immune system effects, which meant that diseases could spread through

populations. You had a certain amount of cancers and tumors, reproductive organ failures, endocrine systems disruptions."Weinberg left Greenpeace in January, although he still functions as an adviser, to take a job with the Environmental Health Fund, a year-old organization based in Boston that is working to build an international

movement addressing issues of health and chemicals. Weinberg is project director of its global health and chemicals project."Many things are needed environmentally, so I don't want to say what I'm choosing to do right now is the most important," Weinberg said.

"But I'm much more interested in working with organizations at a national, regional level in many countries that can cooperate to do this work" regarding toxic chemicals.

Weinberg also has a position with the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois-Chicago, where he is helping to develop an environmental health policy program.

The goal is to provide assistance to public interest groups working on the issue of chemicals around the world.

On a personal, local level, Weinberg and his wife, public relations executive Valerie Denney, recycle and drive their small car infrequently, though he noted that he often travels and airplanes are not environmentally friendly.

He believes widespread recycling and use of mass transit have not taken hold because it's generally inconvenient and only a small number of people will "wear a hair shirt all the time in order to do the right thing."

While the focus on recycling was well meaning, he said, the answers to the problem are more fundamental. "Every Styrofoam cup says `recycle this,' but nobody gives you any way to do so.

"I had to buy some batteries and the package said, `you must recycle these,' so I took them back to the store and asked how to do it and they didn't know. There's no requirement that the manufacturer or sales group has to take it back."

A take-back policy, he added, would lead to products being designed in a manner that would allow parts of them to be used again in manufacturing.

"You can't expect people who just love the Earth or who want a cleaner world to know these things instinctively. The policies have to be worked out." The earlier environmental movement focused on very specific problems at a point when that wasn't a policy concern, Weinberg said. Now corporations put a lot of money into creating environmentally friendly images, making things harder for activists, but Weinberg remains "enthusiastic" about the possibility of change.

"I think everybody was taken by surprise by the reaction in Seattle at the World Trade Organization last year," he said. "Labor was a part of that, but the other main part was driven mainly by environmental forces. The infrastructure is in place to link up policy to [grass roots] constituencies. It's slower and more difficult, but it's the next phase."

last edited March 20, 2002